.

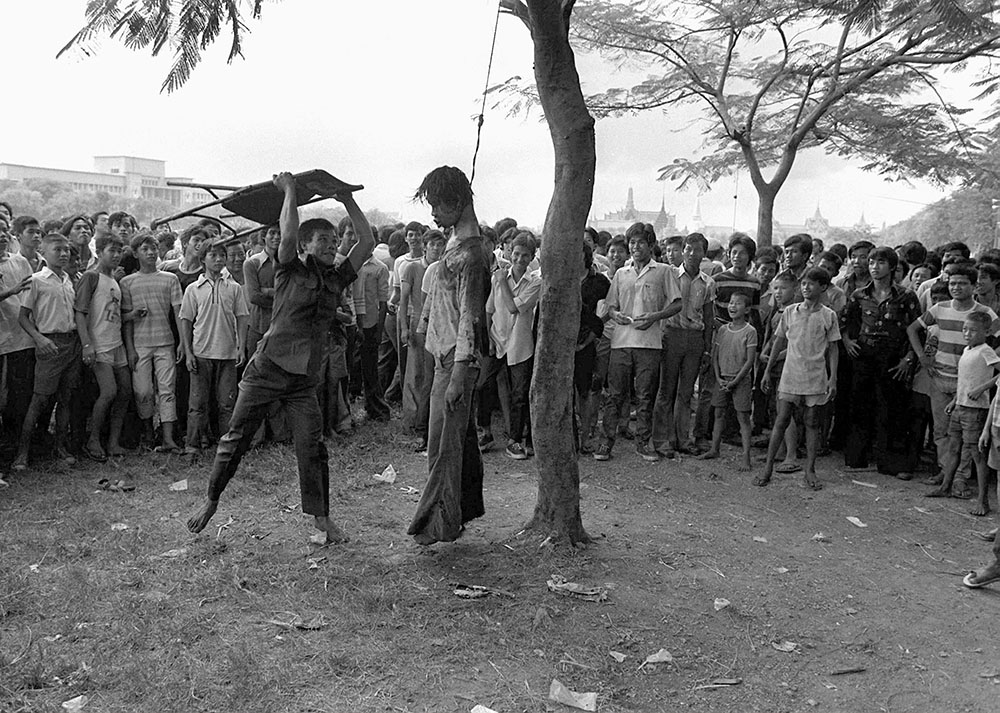

Even as the horrors committed by the Communist Pol Pot regime in Cambodia seeped out into the wider world, the country and its government enjoyed widespread support in Sweden, especially among the ruling Social Democrats and its supporters. The prime minister Olof Palme issued a joint statement with Fidel Castro congratulating the Khmer Rouge, and its leader Pol Pot was frequently portrayed in the Swedish media as a Robin Hood. Government ministers vigorously denied allegations of Khmer Rouge atrocities as exaggerations.

By late 1977, the regime in Phnom Penh was seeking international validation. In November of that year, Burmese dictator Ne Win became the first head of state to visit Phnom Penh since the Khmer Rouge takeover in April 1975, swiftly followed by Romania’s Nicolae Ceausescu. Starting in early 1978, small delegations of Communist-sympathizing westerners were invited to visit Cambodia, via a weekly flight from Beijing to Phnom Penh. Due to the favorable coverage in Sweden, Swedish media and diplomats were given special guided tours and in August 1978, four members of the Sweden–Kampuchea Friendship Association were invited to visit Cambodia. (a member of the delegation was married to a Khmer Rouge diplomat who was stationed in East Germany before being recalled to Cambodia. She asked if she could see her husband, but her request was denied. Unbeknownst to her, her husband had been already been executed a year prior).

.

Among the delegation was Gunnar Bergström, 27, an activist against the Vietnam war. Bergström was jubilant that Cambodia had liberated itself from the capitalist Americans and founded the friendship association and a magazine Kampuchea, with the aim of helping the Khmer Rouge spread its ideals. Bergström was allowed to take photos of the curated locations that the visitors were shown.

The delegation’s requests to meet “new people” (Cambodians who had been evacuated from the cities) were denied, but they did witness children building earthworks, melting down Coca-Cola bottles to make vials for injections, and laboring on boats and was granted an interview with Pol Pot and a subsequent banquet where they dined on oysters with Pol Pot and Foreign Minister Ieng Sary. After a two-week tour, the tour group returned to Europe to contradict accounts by the refugees of overwork, starvation, torture, and mass killings. Bergström dismissed htem as “Western propaganda” and that he saw “smiling peasants” and a society on its way to “an ideal society”.

Following the Vietnamese invasion of Cambodia in December 1978, Bergström and the other members of the Swedish delegation that visited Cambodia advocated for the ouster of Hanoi’s troops and restoration of Pol Pot. But Bergström would soon disavow the Khmer Rouge and acknowledge that he had been taken on a “propaganda tour.”

.

If you like what I do and what I write, or simply wants me to write more, you can support me via Patreon. I had tremendous fun researching and writing Iconic Photos, and the Patreon is a way for this blog to be self-sustaining.Proceeds mainly go to buying photography reference books and support me on my research (re: paywalled articles, trips to various archives). In addition to monthly addenda posts on Patreon, readers who subscribe on Patreon might have access to a few blog posts early; chance to request topics or to participate in some pollsEven if Patreon isn’t your thing, you can support by re-sharing, or tweeting about the blog or the specific posts on here. Thanks for your continued support! Here is the link:https://www.patreon.com/iconicphotos