By its financial obduracy, Germany proves that it has exceedingly falling memory.

While it is often said that the German attitude to fiscal responsibility could be traced back to hyperinflation of 1921-3, it appears that Berlin has missed the big picture that emerged from that national nightmare. There are many differences, of course, but the parallels are also uncanny.

War reparations saddled Germany with huge external debt, just as the Euro has done today in southern European countries. Exporting was the only way out, although Germany had to do it without its main industrial centres in the east and the west, and the southern countries without a flexible exchange rate.

Like Germany today, France was reluctant to help; in Britain, a German bailout was political unpopular. Instead, international creditors demanded public sector cuts; they directed at the military rather than the civil service, but the deflationary effect was no different. The Weimar Government’s later tax increases were as unrealistic as those imposed upon many debtor nations by Germany currently.

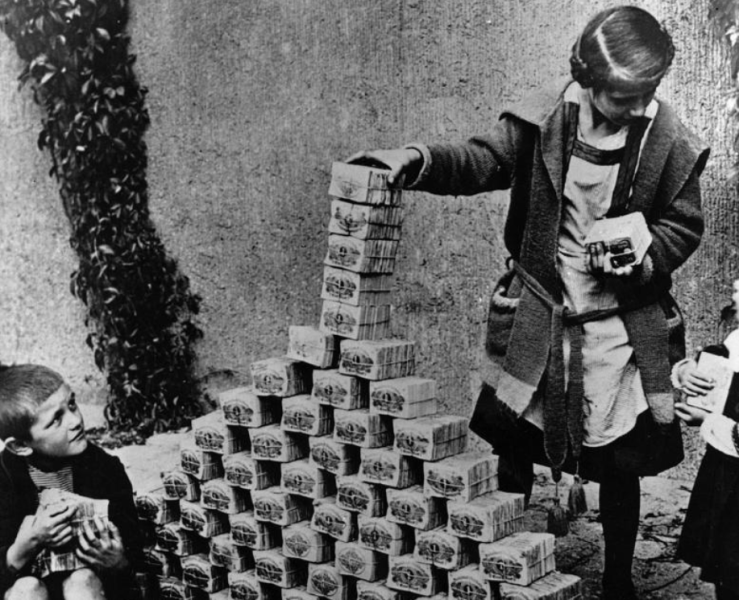

The percentage of government spending covered by taxes rapidly decreased from not-too-spectacular 15% in 1914 to just 0.8% in 1923. This disastrous fall had two causes, both familiar to a modern reader.

Firstly, there was a rampant tax avoidance. Germans evaded taxes in the 1920s, as much as Greeks do today. And as with America today, the war was financed not through tax hikes, but through increased borrowing from international creditors. Therefore, in Germany it almost become a patriotic duty to avoid taxes, which would have gone straight out of the country.

Secondly, successive socialist governments in Germany created a runaway welfare state. Like Greeks, Germans were paid even when they were not working. Although reparations never accounted for more than a third of Germany’s deficit, the government pointed it out as a convenient scapegoat. As always, social ills were blamed on external bogeymen: creditors, speculators and bankers, mostly foreign, mostly Jewish.

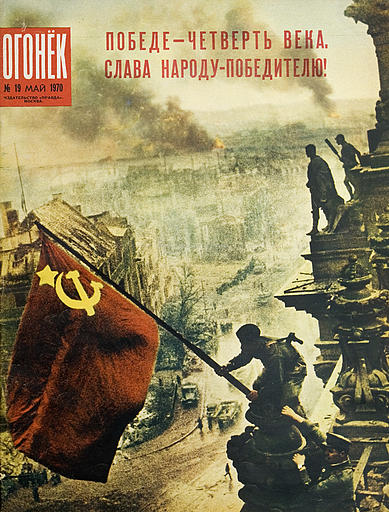

By the time the inflation was stalled in November 1923 with an introduction of a new Mark, the trends were inexorably leading to two seminal events. The German hyper-inflation and the European governments’ inability to deter it was almost a dress rehearsal for the Great Depression. And anxieties and uncertainties these twin disasters unleashed made it easier for the National Socialists to seize power.